Research

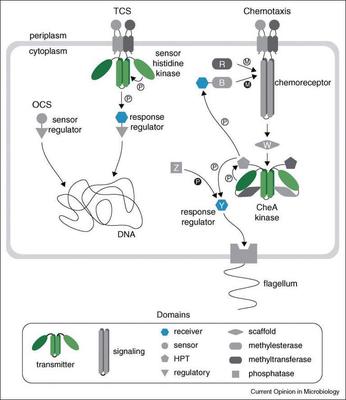

Bacterial chemoreceptors. Bacteria detect their surrounding conditions using specialized molecular machinery built around a signal transduction regulatory system. Its core components that have been extensively studied in the model organism Escherichia coli are well conserved throughout the prokaryotes. This system has remarkable properties, such as signal integration and amplification, high sensitivity over a wide dynamic range, and precise sensory adaptation. Chemoreceptors, also known as methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins (MCPs), are central to these features. Together with kinase CheA and adaptor CheW, chemoreceptors form large complexes arranged in hexagonal arrays at the cell pole. Chemotaxis is associated with virulence in many bacteria including NIH Category A, B, and C Priority Pathogens. Although chemotaxis is critical to pathogenic interactions of bacteria with humans, the molecular details of this system can at present be studied only in a few model organisms. Our work leads to better understanding of chemotaxis in pathogens and consequently to better understanding of virulence. A deeper, mechanistic understanding of how signaling pathways transduce information will be critical in exploiting them as drug targets.

Signal transduction in a genomic perspective. We are interested in unraveling fundamental properties of many other signal transduction systems that control gene expression, second messenger turnover, surface motility and other critical cellular functions. We use evolutionary genomics to compare organization of these systems at different levels in thousands of microbial species using both whole genome and metagenome sequences. We identify and analyze features shared by all signal transduction systems, such as conserved sensory and regulatory domains. This information is captured, stored and maintained in our Microbial Signal Transduction (MiST) database. This unique resource helps the scientific community to extract useful genomic information pertinent to their research on signal transduction.

Using evolutionary information to predict disease-causing mutations. Genetic diseases are mostly caused by deleterious mutations in genes resulting in functionless proteins. Assessment of known DNA variants is straightforward; they are either known as disease-causing or neutral as they are common in populations. However, deciding whether a novel mutation is damaging or benign depends on computational prediction. We reconstruct protein’s history to observe the behavior of a specific residue in the course of evolution. We apply established comparative genomics techniques as well as new approaches to predict whether a newly observed mutation is likely to be benign or damaging. Although this approach has been automated by many groups, in our opinion, none of the automated tools could be equally well applied to every protein. Each protein has its unique evolutionary history that must be carefully analyzed. At this time, human logic and reasoning is superior to automated procedures, but hopefully, as we uncover new principles and rules, full automation of this process will become possible.